Winter Semester Assistance for Excelling in Accounting

FIVE TYPES OF ANALYTICAL PROCEDURES

The usefulness of analytical procedures as audit evidence depends significantly on the auditor developing an expectation of what a recorded account balance or ratio should be, regardless of the type of analytical procedures used. Auditors develop an expec - tation of an account balance or ratio by considering information from prior periods, industry trends, client-prepared budgeted expectations, and nonfinancial information. The auditor typically compares the client’s balances and ratios with expected balances and ratios using one or more of the following types of analytical procedures. In each case, auditors compare client data with:

1. Industry data

2. Similar prior-period data

3. Client-determined expected results

4. Auditor-determined expected results

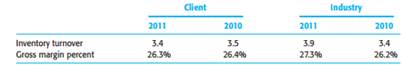

5. Expected results using nonfinancial data Suppose that you are doing an audit and obtain the following information about the client and the average company in the client’s industry:

If we look only at client information for the two ratios shown, the company appears to be stable with no apparent indication of difficulties. However, if we use industry data to develop expectations about the two ratios for 2011, we should expect both ratios for the client to increase. Although these two ratios by themselves may not indicate significant problems, this data illustrates how developing expectations using industry data may provide useful information about the client’s performance and potential misstatements. Perhaps the company has lost market share, its pricing has not been competitive, it has incurred abnormal costs, or perhaps it has obsolete items in inven - tory or made errors in recording purchases. The auditor needs to determine if either of the last two occurred to have reasonable assurance that the financial statements are not misstated. Dun & Bradstreet, Standard and Poor’s, and other analysts accumulate financial information for thousands of companies and compile the data for different lines of business. Many CPA firms purchase this industry information for use as a basis for developing expectations about financial ratios in their audits. The most important benefits of industry comparisons are to aid in understanding the client’s business and as an indication of the likelihood of financial failure. They are less likely to help auditors identify potential misstatements. Financial information collected by the Risk Management Association, for example, is primarily of a type that bankers and other credit analysts use in evaluating whether a company will be able to repay a loan. That same information is useful to auditors in assessing the relative strength of the client’s capital structure, its borrowing capacity, and the likelihood of financial failure. However, a major weakness in using industry ratios for auditing is the difference between the nature of the client’s financial information and that of the firms making up the industry totals. Because the industry data are broad averages, the comparisons may not be meaningful. Often, the client’s line of business is not the same as the industry standards. In addition, different companies follow different accounting methods, and this affects the comparability of data. For example, if most companies in the industry use FIFO inventory valuation and straight-line depreciation and the audit client uses LIFO and double-declining-balance depreciation, comparisons may not be meaningful. This does not mean that industry comparisons should be avoided. Rather, it is an indication of the need for care in using industry data to develop expectations about financial relationships and in interpreting the results. One approach to overcome the limitations of industry averages is to compare the client to one or more benchmark firms in the industry. Suppose that the gross margin percentage for a company has been between 26 and 27 percent for each of the past 4 years but has dropped to 23 percent in the current year. This decline in gross margin should be a concern to the auditor if a decline is not expected. The cause of the decline could be a change in economic conditions. But, it could also be caused by misstatements in the financial statements, such as sales or purchase cutoff errors, unrecorded sales, overstated accounts payable, or inventory costing errors. The decline in gross margin is likely to result in an increase in evidence in one or more of the accounts that affect gross margin. The auditor needs to determine the cause of the decline to be confident that the financial statements are not materially misstated. A wide variety of analytical procedures allow auditors to compare client data with similar data from one or more prior periods. Here are some common examples: Compare the Current Year’s Balance with that of the Preceding Year One of the easiest ways to perform this test is to include the preceding year’s adjusted trial balance results in a separate column of the current year’s trial balance spreadsheet. The auditor can easily compare the current year’s balance and previous year’s balance to decide, early in the audit, whether an account should receive more than the normal amount of attention because of a significant change in the balance. For example, if the auditor observes a substantial increase in supplies expense, the auditor should determine whether the cause was an increased use of supplies, an error in the account due to a misclassification, or a misstatement of supplies inventory. Compare the Detail of a Total Balance with Similar Detail for the Preceding Year If there have been no significant changes in the client’s operations in the current year, much of the detail making up the totals in the financial statements should also remain unchanged. By briefly comparing the detail of the current period with similar detail of the preceding period, auditors often isolate information that needs further examination. Comparison of details may take the form of details over time, such as comparing the monthly totals for the current year and preceding year for sales, repairs, and other accounts, or details at a point in time, such as comparing the details of loans payable at the end of the current year with the detail at the end of the preceding year. In each of these examples, the auditor should first develop an expectation of a change or lack thereof before making the comparison. Compute Ratios and Percent Relationships for Comparison with Previous Years Comparing totals or details with previous years has two shortcomings. First, it fails to consider growth or decline in business activity. Second, relationships of data to other data, such as sales to cost of goods sold, are ignored. Ratio and percent relation - ships overcome both shortcomings. For example, the gross margin is a common percent relationship used by auditors.

(Objective 8-8)

Auditors’ analytical procedures often include the use of general financial ratios during planning and final review of the audited financial statements. These are useful for understanding recent events and the financial status of the business and for viewing the statements from the perspective of a user. The general financial analysis may be effec - tive for identifying possible problem areas, where the auditor may do additional analysis and audit testing, as well as business problem areas in which the auditor can provide other assistance. When using these ratios, auditors must be sure to make appropriate comparisons. The most important comparisons are to those of previous years for the company and to industry averages or similar companies for the same year.

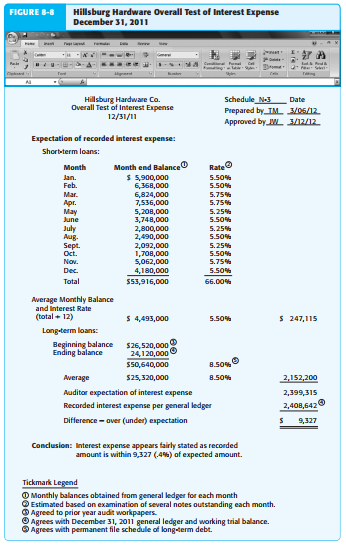

Ratios and other analytical procedures are normally calculated using spreadsheets and other types of audit software, in which several years of client and industry data can be maintained for comparative purposes. Ratios can be linked to the trial balance so hat calculations are automatically updated as adjusting entries are made to the client’s statements. For example, an adjustment to inventory and cost of goods sold affects a large number of ratios, including inventory turnover, the current ratio, gross margin, and other profitability measures. We next examine some widely used financial ratios. The following computations are based on the 2011 financial statements of Hillsburg Hardware Co., which appear in the glossy insert to the textbook. These ratios were prepared from the trial balance in Figure 6-4 on page 150

23. The information is provided in a table for Alpha Company and Bravo Company. Alpha Company Bravo...

The information is provided in a table for Alpha Company and Bravo Company. Alpha Company Bravo Company Balance 12/31/15 Assets $605,000 Liabilities $142,000 Equity 436,000 305,000 Balance 12/31/16 Assets 610,000 Liabilities 184,000 170,000 Equity 460,000 440,000 During the Year: Additional Stock Issued 100,000 Dividends paid to shareholders 60,000 90,000 Revenue 655,000 Expenses 590,000 620,000 What are the amounts for each of the following missing items? 1. Alpha Company's 12/31/15 Liabilities 2. Alpha Company's 12/31/16 Assets 3. Alpha Company's 12/31/16 Additional Stock Issued 4. Bravo Company's 12/31/15 Assets 5. Bravo Company's 12/31/16 Revenues

24. A company sells two products--J and K. The sales mix is expected to be $3 of sales of Product K for.

A company sells two products--J and K. The sales mix is expected to be $3 of sales of Product K for every $1 of sales of Product J. Product J has a contribution margin ratio of 40% whereas Product K has a contribution margin ratio of 50%. Annual fixed expenses are expected to be $120,000. The overall break-even point for the company in dollar sales is expected to be closest to:

25. The following transactions took place in respect of a material item during the month of March:

The following transactions took place in respect of a material item during the month of March:

Date | Receipt Qty. | Rate | Issue Qty. |

March 2 | 200 | 2.00 |

|

March 10 | 300 | 2.40 |

|

March 15 |

|

| 250 |

March 18 | 250 | 2.60 |

|

March 20 |

|

| 200 |

Prepare the Stores Ledger Sheet, pricing the issue at the simple average rate and the weighted average rate.

26. Major League Bat Company manufactures baseball bats. In addition to its work in process inventories,

Major League Bat Company manufactures baseball bats. In addition to its work in process inventories, the company maintains inventories of raw materials and finished goods. It uses raw materials as direct materials in production and as indirect materials. Its factory payroll costs include direct labor for production and indirect labor. All materials are added at the beginning of the process, and conversion costs are applied uniformly throughout the production process. Required: You are to maintain records and produce measures of inventories to reflect the July events of this company. The June 30 balances: Raw Materials Inventory, $25,000; Work in Process Inventory, $8,135 ($2,660 of direct materials and $5,475 of conversion): Finished Goods Inventory, $110,000; Sales, $0; Cost of Goods Sold, $0; Factory Payroll Payable, $0; and Factory Overhead, $0. 1. Prepare journal entries to record the following July transactions and events. a. Purchased raw materials for $125,000 cash (the company uses a perpetual inventory system). b. Used raw materials as follows: direct materials, $52,440, and indirect materials, $10,000. c. Recorded factory payroll payable costs as follows: direct labor, $202,250; and indirect labor, $25,000. d. Paid factory payroll cost of $227,250 with cash (ignore taxes). e. Incurred additional factory overhead costs of $80,000 paid in cash. f. Allocated factory overhead to production at 50% of direct labor costs View transaction list View journal entry worksheet No Transaction General Journal Credit Debit 125,000 Raw materials inventory Cash 125,000 2 b . Work in process inventory Factory overhead Raw materials inventory 52,440 10,000 62,440 C. Work in process inventory Factory overhead Factory wages payable 202,250 25,000 227,250 d Factory wages payable 227,250 Cash 227,250 e. 80,000 Factory overhead Cash 80,000 101,125 Work in process inventory Factory overhead 101,125 2. Information about the July inventories follows. Use this information with that from part 1 to prepare a process cost summary, assuming the weighted average method is used. (Round "Cost per EUP" to 2 decimal places.) 5,000 units 14,800 units 8,000 units Units Beginning inventory Started Ending inventory Beginning inventory Materials-Percent complete Conversion-Percent complete Ending inventory Materials-Percent complete Conversion-Percent complete 100% 75% 100% Total costs to account for: Cost of beginning work in process Total costs to account for $ 0 $ 0 Unit reconciliation: Units to account for: Total units to account for Total units accounted for: Total units accounted for Equivalent units of production (EUP)- weighted average method Units % Materials EUP- Materials % Labor EUP Conversion Total units Cost per equivalent unit of production Materials Conversion Costs EUP Costs EUP Cost per EUP Total cost Total costs • Equivalent units of production Cost per equivalent unit of production (rounded to 2 decimals) Total costs accounted for: Cost of units transferred out: EUP Direct materials Conversion Total costs transferred out Costs of ending goods in process EUP Direct materials Conversion Total cost of ending goods in process Total costs accounted for Cost per EUP $ 0.00 $ 0.00 Total cost $ 3. Using the results from part 2 and the available information, make computations and prepare journal entries to record the following: g. Total costs transferred to finished goods for July. h. Sale of finished goods costing $265,700 for $625,000 in cash. View transaction list View journal entry worksheet No Transaction Credit General journal Finished goods inventory Work in process inventory Debit 241,103 241,103 2 h. 625,000 Cash Sales 625,000 h. 265,700 Cost of goods sold Finished goods inventory 265,700 4. Post entries from parts 1 and 3 to the following general ledger accounts. Raw Materials Inventory Debit Credit Date June 30 Acct. No. 132 Balance 25,000 150,000 87,560 (a) 125,000 Work in Process Inventory Date Debit Credit June 30 (b) 52,440 202,250 101,125 241,103 Acct. No. 133 Balance 8,135 60,575 262,825 363,950 122,847 (b) 62,440 Date Finished Goods Inventory Date Debit Credit June 30 241,103 (h) 265,700 Credit Acct. No. 135 Balance 110,000 351,103 85,403 Factory Wages Payable Debit 227,250 (c) Acct. No. 212 Balance (227,250) (202,250) (429,500) 25,000 (d) 227,250 Sales Debit Date Acct. No. 413 Balance 625,000 Date Credit 625,000 Cost of Goods Sold Debit 265,700 Credit Acct. No. 502 Balance 265,700 Date Credit Factory Overhead Debit 10,000 25,000 80,000 ? Acct. No. 540 Balance 10,000 35,000 115,000 13,875 101,125 5. Compute the amount of gross profit from the sales in July (Add any underapplied overhead to, or deduct any overapplied overhead from, the cost of goods sold.) Gross profit $ 345,425

27. 29. Corn Crunchers has three product lines

29. Corn Crunchers has three product lines. Its only unprofitable line is Corn Nuts, the results of which appear below for 2011:Sales $1,050,000

Variable expenses 690,000

Fixed expenses 450,000

Net loss $ (90,000)

If this product line is eliminated, 30% of the fixed expenses can be eliminated. How much ...

28. flexible budgeting and variance analysis I’m Really Cold Coat Company makes women’s and men’s...

flexible budgeting and variance analysis

I’m Really Cold Coat Company makes women’s and men’s coats. Both products require filler and lining material. The following planning information has been made available:

Standard amount per unit

| women’s Coats | men’s Coats | Standard price per unit |

Filler Liner Standard labor time | 4.0 lbs. 7.00 yds. 0.40 hr. | 5.20 lbs. 9.40 yds. 0.50 hr. | $2.00 per lb. 8.00 per yd. |

| women’s Coats | men’s Coats |

Planned production Standard labor rate | 5,000 units $14.00 per hr. | 6,200 units $13.00 per hr. |

I’m Really Cold Coat Company does not expect there to be any beginning or ending inventories of filler and lining material. At the end of the budget year, I’m Really Cold Coat Company experienced the following actual results:

| women’s Coats | men’s Coats |

Actual production | 4,400 | 5,800 |

| actual price per unit | actual Quantity purchased and used |

Filler | $1.90 per lb. | 48,000 |

Liner | 8.20 per yd. | 85,100 |

| actual Labor Rate | actual Labor hours used |

Women's coats | $14.10 per hr. | 1,825 |

Men's coats | 13.30 per hr. | 2,800 |

The expected beginning inventory and desired ending inventory were realized.

instructions

1. Prepare the following variance analyses for both coats and the total, based on the actual results and production levels at the end of the budget year:

a. Direct materials price, quantity, and total variance.

b. Direct labor rate, time, and total variance.

2.  Why are the standard amounts in part (1) based on the actual production at the end of the year instead of the planned production at the beginning of the year?

Why are the standard amounts in part (1) based on the actual production at the end of the year instead of the planned production at the beginning of the year?

29. Volume based costing and ABC costing

Tioga Company manufactures sophisticated lenses and mirrors used in large optical telescopes. The company is now preparing its annual profit plan. As part of its analysis of the profitability of individual products, the controller estimates the amount of overhead that should be allocated to the individual product lines from the following information.

Lenses | Mirrors | |||

Units produced | 25 | 25 | ||

Material moves per product line | 8 | 18 | ||

Direct-labor hours per unit | 250 | 250 | ||

The total budgeted material-handling cost is $85,500. |

Required: |

1. | Under a costing system that allocates overhead on the basis of direct-labor hours, the material-handling costs allocated to one lens would be what amount? (Omit the "$" sign in your response.) |

Material-handling cost per lens | $ |

2. | Under a costing system that allocates overhead on the basis of direct-labor hours, the material-handling costs allocated to one mirror would be what amount? (Omit the "$" sign in your response.) |

Material-handling cost per mirror | $ |

3. | Under activity-based costing (ABC), the material-handling costs allocated to one lens would be what amount? The cost driver for the material-handling activity is the number of material moves. (Do not round your intermediate calculations. Round your final answers to the nearest dollar amount. Omit the "$" sign in your response.) |

Material-handling cost per lens | $ |

4. | Under activity-based costing (ABC), the material-handling costs allocated to one mirror would be what amount? The cost driver for the material-handling activity is the number of material moves. (Do not round your intermediate calculations. Round your final answers to the nearest dollar amount. Omit the "$" sign in your response.) |

Material-handling cost per mirror | $ |