Top Strategies for Accounting Assignment Excellence

1. On December 1, 2017, Annalise Company had the account balances shown below. The following transa...

On December 1, 2017, Annalise Company had the account balances shown below. The following transactions occurred during December. Dec. 3 Purchased 4,000 units of inventory on account at a cost of $0.74 per unit. 5 Sold 4, 400 units of inventory on account for $0.90 per unit. (It sold 3,000 of the $0.60 units and 1, 400 of the $0.74.) 7 Granted the December 5 customer $180 credit for 200 units of inventory returned costing $120. These units were returned to inventory. 17 Purchased 2, 200 units of inventory for cash at $0.80 each. 22 Sold 2, 100 units of inventory on account for $0.95 per unit. (It sold 2, 100 of the $0.74 units.) Adjustment data: 1. Accrued salaries payable $400. 2. Depreciation $200 per month. Instructions (a) Journalize the December transactions and adjusting entries, assuming Annalise uses the perpetual inventory method. (b) Enter the December 1 balances in the ledger T-accounts and post the December transactions. In addition to the accounts mentioned above, use the following additional accounts: Cost of Goods Sold, Depreciation Expense, Salaries and Wages Expense, Salaries and Wages Payable, Sales Revenue, and Sales Returns and Allowances. (c) Prepare an adjusted trial balance as of December 31, 2017. (d) Prepare an income statement for December 2017 and a classified balance sheet at December 31, 2017. (e) Compute ending inventory and cost of goods sold under FIFO, assuming Annalise Company uses the periodic inventory system. (f) Compute ending inventory and cost of goods sold under LIFO, assuming Annalise Company uses the periodic inventory system.

2. Pratt Corp. started the accounting period with $30,000 of assets, $12,000 of liabilities, and $5,000

Pratt Corp. started the accounting period with $30,000 of assets, $12,000 of liabilities, and $5,000 of retained earnings. During the period, the Retained Earnings account increased by $7,550. The bookkeeper reported that Pratt paid cash expenses of $26,000 and paid a $2,000 cash dividend to stockholders, but she could not find a record of the amount of cash that Pratt received for performing services. Pratt also paid $3,000 cash to reduce the liability owed to a bank, and the business acquired $4,000 of additional cash from the issue of common stock. Required a. Prepare an income statement, statement of changes in stockholders’ equity, year-end balance sheet, and statement of cash flows for the accounting period. b. Determine the percentage of total assets that were provided by creditors, investors, and earnings.

3. Inventory cost flow methods: LIFO liquidation; ratios Cast Iron Grills, Inc., manufactures...

Inventory cost flow methods: LIFO liquidation; ratios

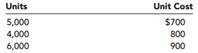

Cast Iron Grills, Inc., manufactures premium gas barbecue grills. The company uses a periodic inventory system and the LIFO cost method for its grill inventory. Cast Iron’s December 31, 2016, fiscal year-end inventory consisted of the following (listed in chronological order of acquisition):

The replacement cost of the grills throughout 2017 was $1,000. Cast Iron sold 27,000 grills during 2017. The company’s selling price is set at 200% of the current replacement cost.

Required:

1. Compute the gross profit (sales minus cost of goods sold) and the gross profit ratio for 2017 assuming that Cast Iron purchased 28,000 units during the year.

2. Repeat requirement 1 assuming that Cast Iron purchased only 15,000 units.

3. Why does the number of units purchased affect your answers to the above requirements?

4. Repeat requirements 1 and 2 assuming that Cast Iron uses the FIFO inventory cost method rather than the LIFO method.

5. Why does the number of units purchased have no effect on your answers to requirements 1 and 2 when the FIFO method is used?

4. What accounts are affected by closing entries? What accounts are not affected?

1. What accounts are affected by closing entries? What accounts are not affected?

2. What two purposes are accomplished by recording closing entries?

3. What are the steps in recording closing entries?

4. What is the purpose of the Income Summary account?

5. Explain whether an error has occurred if a post-closing trial balance includes a Depreciation Expense account.

6. What tasks are aided by a work sheet?

5. (Objectives 26-1, 26-4) Lajod Company has an internal audit department consisting of a manager...

(Objectives 26-1, 26-4) Lajod Company has an internal audit department consisting of a manager and three staff auditors. The manager of internal audits, in turn, reports to the corporate controller. Copies of audit reports are routinely sent to the audit committee of the board of directors as well as to the corporate controller and the individual respon - sible for the area or activity being audited. The manager of internal audits is aware that the external auditors have relied on the internal audit function to a substantial degree in the past. However, in recent months, the external auditors have suggested there may be a problem related to the objectivity of the internal audit function. This objectivity problem may result in more extensive testing and analysis by the external auditors. The external auditors are concerned about the amount of nonaudit work performed by the internal audit department. The percentage of nonaudit work performed by the internal auditors in recent years has increased to about 25% of their total hours worked. A sample of five recent nonaudit activities are as follows:

1. One of the internal auditors assisted in the preparation of policy statements on internal control. These statements included such things as policies regarding sensitive payments and standards of control for internal controls.

2. The bank statements of the corporation are reconciled each month as a regular assignment for one of the internal auditors. The corporate controller believes this strengthens internal controls because the internal auditor is not involved in the receipt and disbursement of cash.

3. The internal auditors are asked to review the budget data in every area each year for relevance and reasonableness before the budget is approved. In addition, an internal auditor examines the variances each month, along with the associated explanations. These variance analyses are prepared by the corporate controller’s staff after consul - tation with the individuals involved.

4. One of the internal auditors has recently been involved in the design, installation, and initial operation of a new computer system. The auditor was primarily con - cerned with the design and implementation of internal accounting controls and the computer application controls for the new system. The auditor also conducted the testing of the controls during the test runs.

5. The internal auditors are often asked to make accounting entries for complex trans - actions before the transactions are recorded. The employees in the accounting department are not adequately trained to handle such transactions. In addition, this serves as a means of maintaining internal control over complex transactions. The manager of internal audits has always made an effort to remain independent of the corporate controller’s office and believes that the internal auditors are objective and independent in their audit and nonaudit activities.

Required

a. Define objectivity as it relates to the internal audit function.

b. For each of the five situations outlined, explain whether the objectivity of Lajod Company’s internal audit department has been materially impaired. Consider each situation independently.

c. The manager of audits reports to the corporate controller.

(1) Does this reporting relationship result in a problem of objectivity? Explain your answer.

(2) Would your answer to any of the five situations in requirement b have changed if the manager of internal audits reported to the audit committee of the board of directors? Explain your answer.*

(Objective 26-1)

(Objective 26-1)

As discussed in Chapter 1, companies employ their own internal auditors to do both financial and operational auditing. During the past two decades, the role of internal auditors has expanded dramatically, primarily because of the increased size and complexity of many corporations. Because internal auditors spend all of their time within one company, they have much greater knowledge about the company’s opera - tions and internal controls than external auditors. That kind of knowledge can be critical to effective corporate governance. The New York Stock Exchange requires its registrants to have an internal audit function, and many other public and private companies also have an internal audit function. The Institute of Internal Auditors professional practices framework provides the following definition of internal auditing:

This definition reflects the changing role of internal auditors. They are expected to provide value to the organization through improved operational effectiveness, while also performing traditional responsibilities, such as:

• Reviewing the reliability and integrity of information

• Ensuring compliance with policies and regulations

• Safeguarding assets

The objectives of internal auditors are considerably broader than the objectives of external auditors, providing flexibility for internal auditors to meet their company’s needs. At one company, internal auditors may focus exclusively on documenting and testing controls for Sarbanes–Oxley Act Section 404 requirements. At another company, internal auditors may serve primarily as consultants, focusing on recommendations that improve organizational performance. Not only may internal auditors focus on different areas, but the extent of internal auditing may vary from one company to another. Internal audit reports are not standardized because the reporting needs vary for each company and the reports are not relied on by external users. Professional guidance for internal auditors is provided by the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), an organization similar to the AICPA that establishes ethical and practice standards, provides education, and encourages professionalism for its approximately 170,000 worldwide members. The IIA has played a major role in the increasing influence of internal auditing. For example, the IIA has established a highly regarded certification program resulting in the designation of Certified Internal Auditor (CIA) for those who meet specific testing and experience requirements. The IIA professional practice framework includes a code of ethics and IIA International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing (known as the “Red Book”). All IIA members and Certified Internal Auditors agree to follow the

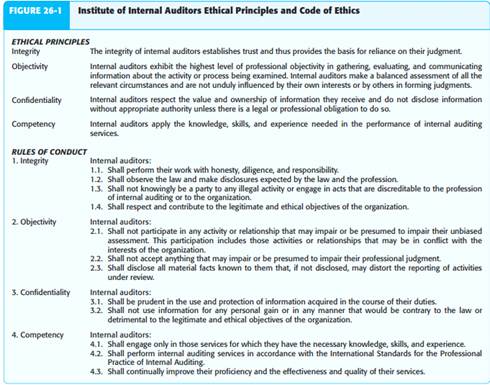

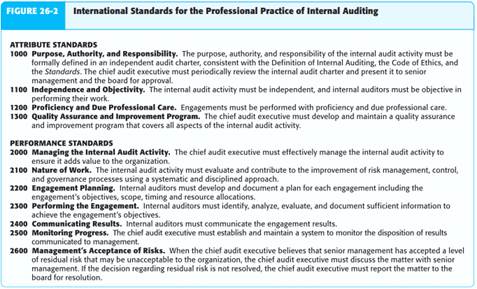

Institute’s Code of Ethics, which requires compliance with the Standards. Figure 26-1 outlines the IIA Code of Ethics, which is based on the ethical principles of integrity, objectivity, confidentiality, and competency. As shown in Figure 26-2 (p. 818), the International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing are divided into attribute standards for internal auditors and audit departments, and performance standards for the conduct and reporting of internal audit activities. The IIA created specific standards within each category. For example, Attribute Standard 1100 on Independence and Objectivity, includes individual standards to address organizational independence (1110), individual objectivity (1120), and impair - ments to independence and objectivity (1130). In addition, the IIA developed specific implementation standards for assurance and consulting engagements. For example, Implementation Standard 1110.A1 provides guid - ance for applying Attribute Standard 1110 on organizational indepen dence for assurance engagements, stating that the internal audit activity should be free from interference in deter mining the scope of internal auditing, performing work, and communicating results. You may want to compare these standards to the AICPA generally accepted auditing standards, as detailed in Table 2-3 on page 35, to note similarities and differ ences. Statements on Internal Auditing Standards (SIASs) are issued by the Internal Auditing Standards Board to provide authoritative interpretations of the standards.

The responsibilities and conduct of audits by internal and external auditors differ in one important way. Internal auditors are responsible to management and the board, while external auditors are responsible to financial statement users who rely on the auditor to add credibility to financial statements. Nevertheless, internal and external auditors share many similarities:

• Both must be competent as auditors and remain objective in performing their work and reporting their results.

• Both follow a similar methodology in performing their audits, including planning and performing tests of controls and substantive tests.

• Both consider risk and materiality in deciding the extent of their tests and evalu - ating results. However, their decisions about materiality and risks may differ because external users may have different needs than management or the board. External auditors rely on internal auditors when using the audit risk model to assess control risk. If internal auditors are effective, the external auditors can significantly reduce control risk and thereby reduce substantive testing. As a result, external auditors may reduce their fees substantially when the client has a highly regarded internal audit function. External auditors typically consider internal auditors effective if they are:

• Independent of the operating units being evaluated

• Competent and well trained

• Have performed relevant audit tests of the internal controls and financial statements Auditing standards permit the external auditor to use the internal auditor for direct assistance on the audit. By relying on the internal audit staff for performing some of the audit testing, external auditors may be able to complete the audit in less time and at a lower fee. When internal auditors provide direct assistance, the external auditor should assess their competence and objectivity and supervise and evaluate their work.

(Objective 26-4)

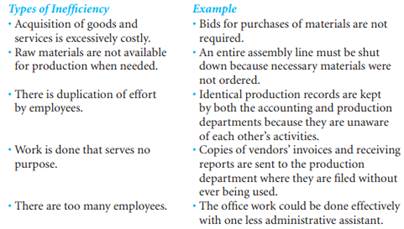

Effectiveness In an operational audit for effectiveness, an auditor, for example, might need to assess whether a governmental agency has met its assigned objective of achieving elevator safety in a city. To determine the agency’s effectiveness, the auditor must establish specific criteria for elevator safety. For example, is the agency’s objective to inspect all elevators in the city at least once a year? Is the objective to ensure that no fatalities occurred as a result of elevator breakdowns, or that no breakdowns occurred? Efficiency Like effectiveness, there must be defined criteria for what is meant by doing things more efficiently before operational auditing can be meaningful. It is often easier to set efficiency than effectiveness criteria if efficiency is defined as reducing cost without reducing effectiveness. For example, if two different production processes manufacture a product of identical quality, the process with the lower cost is considered more efficient. Operational auditing commonly uncovers several types of typical inefficiencies, including:

Management establishes internal controls to help meet its goals. As we discussed in Chapter 10, three concerns are vital to establishing good internal controls:

1. Reliability of financial reporting

2. Efficiency and effectiveness of operations

3. Compliance with applicable laws and regulations

Obviously, the second of these three client concerns directly relates to operational auditing, but the other two also affect efficiency and effectiveness. For example, manage ment needs reliable cost accounting information to decide which products to continue producing and the billing price of products. Similarly, failure to comply with a law, such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, can result in a large fine to the company. Two things distinguish internal control evaluation and testing for financial and operational auditing: purpose and scope. Purpose The purpose of operational auditing of internal control is to evaluate effi - ciency and effectiveness and to make recommendations to management. In contrast, internal control evaluation for financial auditing has two primary purposes: to determine the extent of substantive audit testing required and, when applicable, to report on the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting. For both financial and operational auditing, the auditors may evaluate the control procedures in the same way, but for different purposes. An operational auditor might test whether internal verification procedures for duplicate sales invoices are effective to ensure that the company does not offend customers, but also to collect all receivables. A financial auditor often does the same internal control tests, but the primary purpose is to reduce confirmation of accounts receivable or other substantive tests. (A secondary purpose of many financial audits is also to make operational recommendations to management.) Scope The scope of operational auditing concerns any control affecting efficiency or effectiveness, while the scope of internal control evaluation for financial audits is restricted to the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting and its effect on the fair presentation of financial statements. For example, an operational audit can focus on policies and procedures established in the marketing department to deter - mine the effectiveness of catalogs in marketing products.Operational audits fall into three broad categories: functional, organizational, and special assignments. In each case, part of the audit is likely to concern evaluating internal controls for efficiency and effectiveness. Functional Audits Functions are a means of categorizing the activities of a business, such as the billing function or production function. Functions may be categorized and subdivided many different ways. For example, the accounting function may be sub - divided into cash disbursement, cash receipt, and payroll disbursement functions. The payroll function may be subdivided into hiring, timekeeping, and payroll disbursement functions. A functional audit deals with one or more functions in an organization, concerning, for example, the efficiency and effectiveness of the payroll function for a division or for the company as a whole. A functional audit has the advantage of permitting specialization by auditors. Certain auditors within an internal audit staff can develop considerable expertise in an area, such as production engineering. They can be more efficient and effective by spending all their time auditing in that area. A disadvantage of functional auditing is the failure to evaluate interrelated functions. For example, the production engineering function interacts with manufacturing and other functions in an organization. Organizational Audits An operational audit of an organization deals with an entire organizational unit, such as a department, branch, or subsidiary. An organizational audit emphasizes how efficiently and effectively functions interact. The plan of organi - zation and the methods to coordinate activities are important in this type of audit. Special Assignments In operational auditing, special assignments arise at the request of management for a wide variety of audits, such as determining the cause of an ineffective IT system, investigating the possibility of fraud in a division, and making recommendations for reducing the cost of a manufactured product.