Accounting Research and Analysis: Assignment Assistance Tips

1. (Objective 22-3) Describe the duties of a stock registrar and a transfer agent. How does the use...

(Objective 22-3) Describe the duties of a stock registrar and a transfer agent. How does the use of their services affect the client’s internal controls?

(Objective 22-3)

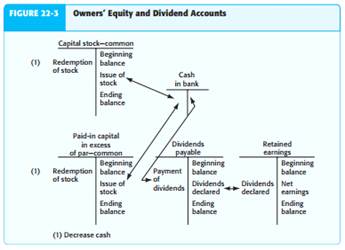

OWNERS’ EQUITY

There is an important difference in the audit of owners’ equity between a publicly held corporation and a closely held corporation. In most closely held corporations, which typically have few shareholders, occasional, if any, transactions occur during the year for capital stock accounts. The only transactions entered in the owners’ equity section are

likely to be the change in owners’ equity for the annual earnings or loss and the declaration of dividends, if any. Closely held corporations rarely pay dividends, and auditors spend little time verifying owners’ equity, even though they must test the corporate records. For publicly held corporations, however, the verification of owners’ equity is more complex because of the larger numbers of shareholders and frequent changes in the individuals holding the stock. The rest of this chapter deals with tests for verifying the major owners’ equity accounts in a publicly held corporation, including:

• Capital and common stock

• Paid-in capital in excess of par

• Retained earnings and related dividends Figure 22-3 (p. 719) provides an overview of the specific owners’ equity accounts discussed. The objective for each is to determine whether:

• Internal controls over capital stock and related dividends are adequate

• Owners’ equity transactions are correctly recorded, as defined by the six transaction-related audit objectives

• Owners’ equity balances are properly recorded, as defined by the eight balancerelated audit objectives, and properly presented and disclosed, as defined by the four presentation and disclosure-related audit objectives for owners’ equity accounts Other accounts in owners’ equity are verified in much the same way as these.

Several internal controls are important for owners’ equity activities. We discuss several of these in the following sections. Proper Authorization of Transactions Because each owners’ equity transaction is typically material, many of these transactions must be approved by the board of directors. The following types of owners’ equity transactions usually require specific authori zation:

• Issuance of Capital Stock. The authorization includes the type of equity to issue (such as preferred or common stock), number of shares to issue, par value of the stock, privileged condition for any stock other than common, and date of the issue.

• Repurchase of Capital Stock. The repurchase of common or preferred shares, the timing of the repurchase, and the amount to pay for the shares should all be approved by the board of directors.

• Declaration of Dividends. The board of directors must authorize the form of the dividends (such as cash or stock), the amount of the dividend per share, and the record and payment dates of the dividends.

Proper Record Keeping and Segregation of Duties When a company maintains its own records of stock transactions and outstanding stock, the internal controls must be adequate to ensure that:

• Actual owners of the stock are recognized in the corporate records

• The correct amount of dividends is paid to the stockholders owning the stock as of the dividend record date

• The potential for misappropriation of assets is minimized The proper assignment of personnel, adequate record-keeping procedures, and independent internal verification of information in the records are useful controls for these purposes. The client should also have well-defined policies for preparing stock certificates and for recording capital stock transactions. When issuing and recording capital stock, the client must comply with both the state laws governing corporations and the requirements in the corporate charter. The par value of the stock, the number of shares the company is authorized to issue, and state taxes on the issue of capital stock all affect issuance and recording. As a control over capital stock, most companies maintain stock certificate books and a shareholders’ capital stock master file. A capital stock certificate record records the issuance and repurchase of capital stock for the life of the corporation. The record for a capital stock transaction includes the certificate number, the number of shares issued, the name of the person to whom it was issued, and the issue date. When shares are repurchased, the capital stock certificate book should include the cancelled certificates and the date of their cancellation. A shareholders’ capital stock master file is the record of the outstanding shares at any given time. The master file acts as a check on the accuracy of the capital stock certificate record and the common stock balance in the general ledger. It is also used as the basis for the payment of dividends. The disbursement of cash for the payment of dividends should be controlled in much the same manner as the preparation and payment of payroll, which we described in Chapter 20. Internal controls affecting dividend payments may include:

• Dividend checks are prepared from the capital stock certificate record by someone who is not responsible for maintaining the capital stock records.

• After the checks are prepared, there is independent verification of the stockholders’ names and the amounts of the checks and a reconciliation of the total amount of the dividend checks with the total dividends authorized in the minutes.

• A separate imprest dividend account is used to prevent the payment of a larger amount of dividends than was authorized. Independent Registrar and Stock Transfer Agent Any company with stock listed on a securities exchange is required to engage an independent registrar as a control to prevent the improper issue of stock certificates. The responsibility of an independent registrar is to make sure that stock is issued by a corporation in accordance with the capital stock provisions in the corporate charter and the authorization of the board of directors. When there is a change in the ownership of the stock, the registrar is respon - sible for signing all newly issued stock certificates and making sure that old certificates are received and cancelled before a replacement certificate is issued. Most large corporations also employ the services of a stock transfer agent to main - tain the stockholder records, including those documenting transfers of stock ownership. The employment of a transfer agent helps strengthen control over the stock records by putting the records in the hands of an independent organization and helps reduce the cost of record keeping by using a specialist. Many companies also have the transfer agent disburse cash dividends to shareholders, further improving internal control.

2. Cost of Materials Issuances Under the FIFO Method An incomplete subsidiary ledger of materials inven

Cost of Materials Issuances Under the FIFO Method An incomplete subsidiary ledger of materials inventory for May is as follows: a. Complete the materials issuances and balances for the materials subsidiary ledger under FIFO. Received Issued Balance Receiving Report Quantity Unit Price Materials Requisition Number Quantity Amount Date Quantity Unit price Amount Number $8,550 May 1 May 4 40 130 $32.00 8,550 285 285 130 235 x 4,160 365 $ 33,215 X ( C $30.00 30.00 32.00 32.00 32.00 38.00 38.00 44 May 10 May 21 110 38.00 110 14,180 97 1 00 9,700 * May 27 C Feedback Check My Work a. Calculate the amount of each materials issue, using FIFO. In the Balance section, separate each different unit price and its quantity b. Determine the materials inventory balance at the end of May. Feedback C. Journalize the summary entry to transfer materials to work in process. Feedback Check My Work c. Increase work in process and decrease materials for the total of issuances found in Req. a. d. Comparing as reported in the materials ledger with predetermined order points would enable management to order materials before a(n) causes idle time. Feedback Check My Work d. What is the benefit of having materials as needed? Feedback Check My Work Partially correct

3. 127. Activity-based-costing analysis makes no distinction between a. direct-materials inventory and.

127. Activity-based-costing

analysis makes no distinction between

a. direct-materials inventory and

work-in-process inventory.

b. short-run variable costs and short-run

fixed costs.

c. parts of the supply chain.

d. components of the value chain.

128. Activity-based

budgeting makes it easier

a. to determine a rolling budget.

b. to prepare pro forma financial statements.

c. to determine how to reduce costs.

d. to execute a financial budget.

129. Activity-based budgeting does NOT require

a. knowledge

of the organization’s activities.

b. specialized

expertise in financial management and control.

c. knowledge

about how activities affect costs.

d. the

ability to see how the organization’s different activities fit together.

130. Activity-based

budgeting

a. uses one cost driver such as direct

labor-hours.

b. uses only output-based cost drivers such

as units sold.

c. focuses on activities necessary to produce

and sell products and services.

d. classifies costs by functional area within

the value chain.

131. Activity-based

budgeting includes all the following steps EXCEPT

a. determining demands for activities from

sales and production targets.

b. computing the cost of performing

activities.

c. determining a separate cost-driver rate

for each department.

d. describing the budget as costs of

activities rather than costs of functions.

132. Variances

between actual and budgeted amounts can be used to

a. alert managers to potential problems and

available opportunities.

b. inform managers about how well the company

has implemented its strategies.

c. signal that company strategies are

ineffective.

d. do all of the above.

133. A

maintenance manager is MOST likely responsible for

a. a

revenue center.

b. an

investment center.

c. a

cost center.

d. a

profit center.

134. The

regional sales office manager of a national firm is MOST likely responsible for

a. a

revenue center.

b. an

investment center.

c. a

cost center.

d. a

profit center.

135. A

regional manager of a restaurant chain in charge of finding additional

locations for expansion is MOST likely responsible for

a. a

revenue center.

b. an

investment center.

c. a

cost center.

d. a

profit center.

136. The

manager of a hobby store that is part of a chain of stores is MOST likely

responsible for

a. a

revenue center.

b. an

investment center.

c. a

cost center.

d. a

profit center.

4. (Objective 18-6) In testing the cutoff of accounts payable at the balance sheet date, explain why...

(Objective 18-6) In testing the cutoff of accounts payable at the balance sheet date, explain why it is important that auditors coordinate their tests with the physical obser - vation of inventory. What can the auditor do during the physical inventory to enhance the likelihood of an accurate cutoff?

(Objective 18-6)

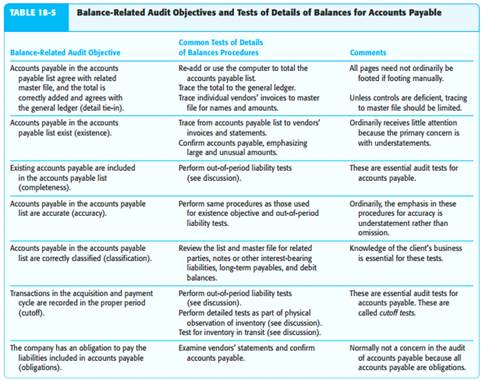

There is an important difference in emphasis in the audit of liabilities and assets. When auditors verify assets, they emphasize overstatements through verifi cation by confirmation, physical examination, and examination of supporting docu ments. The opposite approach is taken in verifying liability balances; that is, the main focus is on understated or omitted liabilities. The difference in emphasis in auditing assets and liabilities results directly from the legal liability of CPAs. If equity investors, creditors, and other users determine subse - quent to the issuance of the audited financial statements that earnings and owners’ equity were materially overstated, a lawsuit against the CPA firm is fairly likely. Because an overstatement of owners’ equity can arise either from an overstatement of assets or an understatement of liabilities, it is natural for CPAs to emphasize those two types of misstatements. Auditors should not ignore the possibility that assets are understated or liabilities are overstated, and should design tests to detect material understatements of earnings and owners’ equity, including those arising from material overstatements of accounts payable. We will use the same balance-related audit objectives from Chapter 16 that we applied to verifying accounts receivable, as they also apply to liabilities, with three minor modifications:

1. The realizable value objective is not applicable to liabilities. Realizable value applies only to assets.

2. The rights aspect of the rights and obligations objective is not applicable to liabilities. For assets, the auditor is concerned with the client’s rights to the use and disposal of the assets. For liabilities, the auditor is concerned with the client’s obligations for the payment of the liability. If the client has no obliga - tion to pay a liability, it should not be included as a liability.

3. For liabilities, there is emphasis on the search for understatements rather than for overstatements, as we just discussed.

Table 18-5 (p. 616) includes the balance-related audit objectives and common tests of details of balances procedures for accounts payable. The auditor’s actual audit procedures vary considerably depending on the nature of the entity, the materiality of accounts payable, the nature and effectiveness of internal controls, and inherent risk. As auditors perform test of details of balances for accounts payable and other liability accounts they may also gather evidence about the four presentation and disclosure objectives, especially when performing completeness objective tests. Other procedures related to presentation and disclosure objectives are done as part of procedures to complete the audit, which we will discuss in Chapter 24.

Out-of-Period Liability Tests Because of the emphasis on understatements in liability accounts, out-of-period liability tests are important for accounts payable. The extent of tests to uncover unrecorded accounts payable, often called the search for unrecorded accounts payable, depends heavily on assessed control risk and the materiality of the potential balance in the account. The same audit procedures used to uncover unrecorded payables are applicable to the accuracy objective. The following are typical audit procedures: Examine Underlying Documentation for Subsequent Cash Disbursements Auditors examine supporting documentation for cash disbursements subsequent to the balance sheet date to determine whether a cash disbursement was for a current period liability. If it is a current period liability, the auditor should trace it to the accounts payable trial balance to make sure it is included. The receiving report indicates the date inventory was received and is therefore an especially useful document. Similarly, the vendor’s invoice usually indicates the date services were provided. Auditors often examine documentation for cash disbursements made in the subsequent period for several weeks after the balance sheet date, especially when the client does not pay bills on a timely basis. Examine Underlying Documentation for Bills Not Paid Several Weeks After the YearEnd Auditors carry out this procedure in the same manner as the preceding one and for the same purpose. This procedure differs in that it is done for unpaid obligations near the end of the audit rather than for obligations that have already been paid.

For example, in an audit with a March 31 year-end, assume the auditor examines the supporting documentation for checks paid through June 28. Bills that are still unpaid on June 28 should be examined to determine whether they are obligations at March 31. Trace Receiving Reports Issued Before Year-End to Related Vendors’ Invoices All merchandise received before the year-end of the accounting period should be included as accounts payable. By tracing receiving reports issued up to year-end to vendors’ invoices and making sure that they are included in accounts payable, the auditor is testing for unrecorded obligations. Trace Vendors’ Statements That Show a Balance Due to the Accounts Payable Trial Balance If the client maintains a file of vendors’ statements, auditors can trace any statement that has a balance due at the balance sheet date to the listing to make sure it is included as an account payable. Send Confirmations to Vendors with Which the Client Does Business Although the use of confirmations for accounts payable is less common than for accounts receivable, auditors use them occasionally to test for vendors omitted from the accounts payable list, omitted transactions, and misstated account balances. Sending confirmations to active vendors for which a balance has not been included in the accounts payable list is a useful means of searching for omitted amounts. This type of confirmation is commonly called a zero balance confirmation. Additional discussion of confirmation of accounts payable is deferred until the end of this chapter. Cutoff Tests Accounts payable cutoff tests are done to determine whether transactions recorded a few days before and after the balance sheet date are included in the correct period. The five out-of-period liability audit tests we just discussed are all cutoff tests for acquisitions, but they emphasize understatements. For the first three procedures, it is also appropriate to examine supporting documentation as a test of overstatement of accounts payable. For example, the third procedure tests for understatements (unrecorded accounts payable) by tracing receiving reports issued before year-end to related vendors’ invoices. To test for overstatement cutoff amounts, the auditor should trace receiving reports issued after year-end to related invoices to make sure that they are not recorded as accounts payable (unless they are inventory in transit, which is discussed shortly). We’ve already discussed most cutoff tests in the preceding section, but we will focus on two aspects here: the relationship of cutoff to physical observation of inventory and the determination of the amount of inventory in transit. Relationship of Cutoff to Physical Observation of Inventory In determining that the accounts payable cutoff is correct, it is essential that the cutoff tests be coordinated with the physical observation of inventory. For example, assume that an inventory acquisition for $400,000 is received late in the afternoon of December 31, after the physical inventory is completed. If the acquisition is included in accounts payable and purchases but excluded from ending inventory, the result is an understatement of net earnings of $400,000. Conversely, if the acquisition is excluded from both inventory and accounts payable, there is a misstatement in the balance sheet, but the income statement is correct. The only way the auditor will know which type of misstatement has occurred is to coordinate cutoff tests with the observation of inventory. The cutoff information for acquisitions should be obtained during the physical obser vation of inventory. At that time, the auditor should review the procedures in the receiving department to determine that all inventory received was counted, and the auditor should record in the audit documentation the last receiving report number of inventory included in the physical count. Subsequent to the physical count date, the auditor should then test the accounting records for cutoff. The auditor should trace the previously documented receiving report numbers to the accounts payable records to verify that they are correctly included or excluded. For example, assume that the last receiving report number representing inventory included in the physical count was 3167. The auditor should record this docu ment number and subsequently trace it and several preceding numbers to their related vendors’ invoices and to the accounts payable list or the accounts payable master file to determine that they are all included. Similarly, accounts payable for acquisitions recorded on receiving reports with numbers larger than 3167 should be excluded from accounts payable. When the client’s physical inventory takes place before the last day of the year, the auditor must still perform an accounts payable cutoff at the time of the physical count in the manner described in the preceding paragraph. In addition, the auditor must verify whether all acquisitions that took place between the physical count and the end of the year were added to the physical inventory and accounts payable. For example, if the client takes the physical count on December 27 for a December 31 year-end, the cutoff information is taken as of December 27. After the physical count date, the auditor must first test to determine whether the cutoff was accurate as of December 27. After deter - mining that the December 27 cutoff is accurate, the auditor must test whether all inventory received subsequent to the physical count, but on or before the balance sheet date, was added to inventory and accounts payable by the client. Inventory in Transit In accounts payable, auditors must distinguish between acquisi - tions of inventory that are on an FOB destination basis and those that are made FOB origin. For FOB destination, title passes to the buyer when the inventory is received, so only inventory received on or before the balance sheet date should be included in inventory and accounts payable at year-end. When an acquisition is FOB origin, the company must record the inventory and related accounts payable in the current period if shipment occurred on or before the balance sheet date. Auditors can determine whether inventory has been acquired FOB destination or origin by examining vendors’ invoices. Auditors should examine invoices for merchandise received shortly after year-end to determine whether they were on an FOB origin basis. For those that were, and when the shipment dates were on or before the balance sheet date, the inventory and related accounts payable must be recorded in the current period if the amounts are material.